Baghrir: The Thousand-Hole crêpe That Divides the Maghreb

The Weekend Crêpe You Didn’t Know You Needed: How to Master Baghrir. Semolina shopping on Saturday, bubbles on Sunday

Marahba, hello!

Welcome to Kalām—Arabic for “words and conversation”—a publication for anyone hungry to explore Tunisia through its food, art, and culture. I'm Boutheina Ben Salem, a French-Tunisian cook, curator, and founder of the BabéldeB supper club.

Each month, I’ll bring you a table of tastes & tales: recipes you’ll want to cook for a lifetime, cultural dispatches that test what you think you know about North Africa, and curated finds.

For now, Kalām is free, like all the best conversations should be.

I was obsessed with baghrir before I even knew it was a thing people fought over.

The first time I tried one, I was standing in my mum’s Moroccan friend tata Ghislaine’s kitchen, watching her drown a stack in honey and melted butter mixed with smen. The baghrir drank it in, greedily. One bite—warm, airy, collapsing in my mouth before I even had time to chew—and that was it.

Hooked for life.

Every Saturday became baghrir day. Tata Ghislaine had me whisking, blending, testing for the perfect bubbles. Until my mum’s Algerian friend caught wind of it. She wasn’t having it. One day, she turned up unannounced, dropped a big plate covered with a tea towel on the table, and said nothing.

I lifted the towel. Baghrir.

Turns out Algeria, too, has its claim on baghrir. Same airy texture, same honey-soaked goodness.

Years later, in Tunis, I was cocky about my baghrir skills, showing off in my cousin’s flat. I wanted to impress her flatmates. That’s when one of them casually said, “Oh, we make those too, back home in Béja.”

You don’t say.

Béja. North-west Tunisia. Where baghrir—sorry, ghreyef—is also a thing.

And that’s when I realised. This wasn’t just Moroccan. Or Algerian. It was a whole Maghrebi battleground.

Back then, I had no idea that baghrir sat at the centre of one of North Africa’s most passionately contested culinary rivalries. Call it a Mediterranean temper.

North Africans take food seriously. Try getting a group of Tunisians, Algerians and Moroccans to agree on who makes the best couscous. And I mean that literally. At the Kouss-Kouss Festival in Marseille, we wore T-shirts that read: “Le meilleur couscous, c’est celui de ma mère” , the best couscous? It’s my mum’s couscous.

And if you thought couscous was contentious, wait until you get to baghrir.

The comment sections under baghrir recipes? Absolute carnage. Moroccans and Algerians lobbing verbal grenades, each staking claim to historical ownership, while Tunisians slip in with a diplomatic, “We make it too.”

Yet for all the bickering, the truth is simple: baghrir is a staple across the Maghreb, rooted in Berber cuisine, which long predates modern borders. It goes by many names—kourssa, khringo, edarnan, tiƴrifin, tibou'jajine, ghreyef.

Call it Algerian, Moroccan, Tunisian—call it yours. Because when it’s warm, fresh off the pan, and soaked in honey, no one cares who made it first.

Baghrir: How to Make the Maghreb’s Iconic Thousand-Hole Crêpe

This recipe has been tested by the most hopeless of home cooks—my husband. Trust me, if he managed to make lacy baghrir, so will you.

(And yes, I supervised.)

Before you start, read the whole recipe, including the troubleshooting section at the end.

Baghrir is simple: semolina, flour, water, yeast, baking powder. No fat, no fuss. Back home, people measure everything with a drinking glass—two parts semolina, one part flour, more or less four parts water to dry ingredients. A tablespoon of dry yeast, and Alsa or La Pâtissière baking powder, sugar, salt—et voilà.

That’s how I learned, with Tata Ghislaine watching over every step.

Some use only extra-fine semolina, but I like a touch of flour for texture.

Yalla, to the recipe.

A Few Notes Before You Start:

Water quantity may vary depending on the type of semolina and flour you use.

Flour: I use French T45 flour (ideal for crêpes), which in UK supermarkets is sold as 00 flour or pastry flour. All-purpose flour works well.

Semolina: Extra fine semolina yields the best texture, but fine semolina works too. It’s readily available in North African, Turkish, and Kurdish shops.

Yeast: The recipe calls for both dry active yeast and baking powder. Make sure your yeast is active.

Pan: A thick-based non-stick pan with good heat distribution is ideal, but any non-stick pan will do. Even if your baghrir are not textbook perfect, they’ll still be delicious.

Before cooking, prepare a large plate or tray lined with a tea towel. Do not stack baghrir while they’re hot—or they’ll stick together.

Makes ~15 baghrir (12cm diameter)

Ingredients:

250g extra fine or fine semolina

125g cake and pastry flour (or sifted all-purpose flour)

5g dry active yeast

14g baking powder

4g sugar

6g salt

600g lukewarm water (adjust based on your flour and semolina absorption) plus 15g of orange blossom water (optional, but lovely)

For the butter & honey syrup

100g of butter (or as much as you like)

1 heaped tablespoon of honey

Zest of an orange

Method:

1. Activate the yeast (optional, but recommended).

Dissolve the sugar in a small amount of lukewarm water. Add the dry yeast and let sit until foamy (5–10 min).

2. Mix the dry ingredients.

In a deep bowl, whisk together the semolina, flour, and salt. Do not add the baking powder yet.

3. Combine wet and dry ingredients.

Add the activated yeast mixture to the dry ingredients. Gradually pour in the remaining water while whisking by hand.

The batter should be slightly thicker than crêpe batter but thinner than pancake batter. This is where I lost my clueless husband. He has never made crêpes or pancakes. Sigh.

So, basically—if unsure, err on the thicker side. You can adjust later.

4. Blend the batter.

Transfer the batter to a blender. If it feels too thick, add lukewarm water 1 tbsp at a time (but don’t overdo it yet).

Blend on high speed for 5 minutes, until the batter is smooth, slightly frothy, and free of grit.

If using a standard blender, be cautious. A too-thick batter can strain the motor. If it struggles, add a touch more water.

5. Add baking powder & strain the batter.

After blending, mix in the baking powder and blend again for 30 seconds—just enough to incorporate.

Strain the batter through a fine sieve into a clean bowl to remove lumps and ensure a smooth texture.

6. Rest the batter.

Cover and let it sit for 15–30 minutes, until the surface is bubbly.

7. Cook the baghrir.

Preheat a non-stick pan over medium heat. It must be hot before you start.

Gently stir the batter. Using a ladle or measuring cup, pour the batter into the pan. Pour as you would a pancake, depending on the size you want.

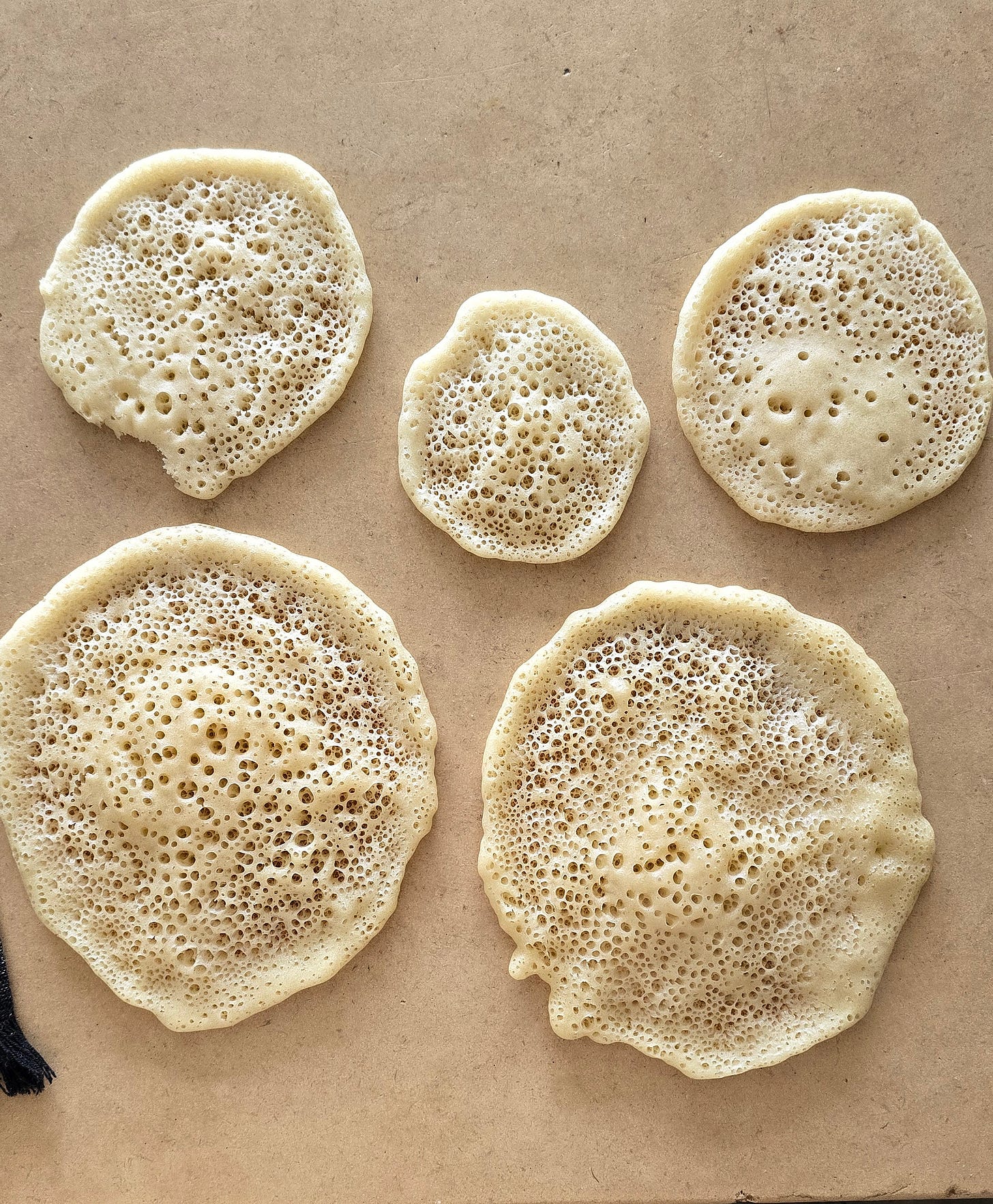

If the batter is just right, tiny bubbles will rise to the surface, spreading like lace across the pan.

If nothing happens, well—either:

The pan is too cold

The batter is too thick

The batter is underproofed

Check the troubleshooting section to fix it. You will get it right eventually.

8. Cook on one side only. Baghrir is cooked without flipping.

Read this twice. Because once was apparently not enough for my clueless husband. Once the surface is dry and set, remove with a spatula and place on the prepared tray with a tea towel.

10. Make the syrup and serve

Melt the butter over low heat, add the orange zest, then stir in the honey. Do not cook the honey—just let it melt into the butter. Pour the syrup over the baghrir and sprinkle some salt flakes. You can also serve the syrup on the side, roll up the baghrir and dip.

Baghrir has a mild flavour on its own, but it truly shines when drizzled with honey or syrup alongside melted butter. Experiment with Jam and marmalades.

Troubleshooting Baghrir: Common Issues and Fixes

The most common problems with baghrir come down to three key factors: hydration, proofing, and heat distribution. If your batter was blended properly (see Step 4), but the results aren’t quite right, here’s how to fix it.

Baghrir barely bubbles & has dense patches

Linked to: Hydration & Proofing

Solution

Check the consistency. Baghrir batter should be thicker than crêpe batter but thinner than pancake batter.

If it’s too thick, bubbles can’t rise properly. Add lukewarm water, 1 tbsp at a time, whisking well. Test again.

If baghrir still has dense spots, it’s underproofed. Cover batter and let it rest longer until bubbly. (In colder temperatures, this will take more time.)

Uneven holes

Linked to: Heat Distribution & Proofing

Solution:

If holes appear uneven or some areas are dense while others bubble up, your pan is likely too hot. Reduce heat to medium, let the pan cool slightly, and try again.

If the issue persists after 3 baghrir, your batter is still underproofed. Cover and let it rest longer until it looks visibly bubbly and airy.

Issues with heat distribution (inconsistent results from batch to batch)

Solution:

If using a thin non-stick pan, you’ll need to constantly adjust the heat.

One trick (admittedly not great for your pan, but effective) is to briefly run the bottom of the pan under cold water every 4 to 5 baghrir. This prevents overheating and helps with consistent hole formation.

Like anything, the more you make baghrir, the easier it gets.

But once you get a feel for it, you stop thinking in measurements and start thinking in movement, in texture. You’ll know it’s right when the batter spreads effortlessly, when the bubbles lace across the surface.

That’s when you’ve nailed it.

B x